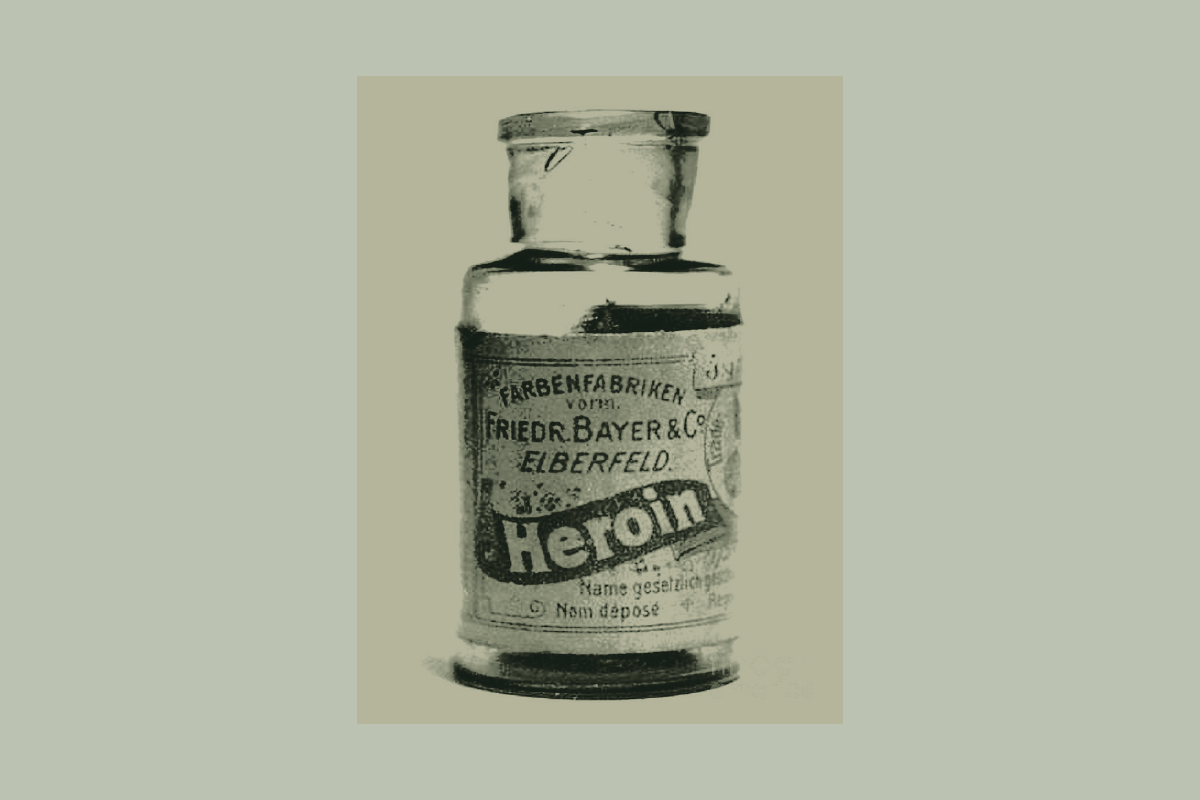

We don’t sell heroin over the counter anymore.

March 1, 2021

Considering the advancements we have all witnessed in technology, energy, communication, society, dress code (including beards becoming acceptable in the workplace) and behavioural science; organisational management has remained fairly unaltered for most businesses over the last 100 years.

The first era of organisational management structure as we know it, came about around the turn of the 20th century. Scaled-up mass production processes in factories required managers to assist business owners in organising, directing and controlling their newly expanded workforce. Managers had to find innovative ways of motivating their employees to perform, and at the time they opted for bureaucratic hierarchies, with standardised rules as part of their management theory. Command and control was born.

Management theory evolved in the mid 1900s as many employees became ‘knowledge workers’. They became valuable for the information and knowledge they had acquired as opposed to their ability to execute a manual task. Knowledge workers required a different style of management as business owners recognised that in order to retain them they required motivation and engagement… a simple pay cheque was not enough.

Then, Milton Friedman, who became the Nobel Prize winner for Economic Sciences in 1976, authored an essay for The New York Times in 1970 which essentially argued that the only social responsibility a business had was to make profit for its shareholders. He specifically argued that businesses had no responsibility to the public or society. The Friedman Doctrine, as it was known, became the modern interpretation of capitalism and Friedman castigated those organisations who took seriously their “responsibilities for providing employment, eliminating discrimination, avoiding pollution and whatever else may be the catch words of the contemporary crop of reformers”. This was music to many businessmen’s ears, and they clung on to it – liberated from difficult moral decisions and feeling invincible as long as they made profits.

But command and control management and focusing solely on the delivery of profit overlooked the fact that employees increasingly sought autonomy, meaning and purpose in the work that they do, beyond delivering shareholder profits. Organisations are still supposedly, and often superficially, wrestling with the notion that their employee’s happiness comes before profits, but few take action which demonstrates this.